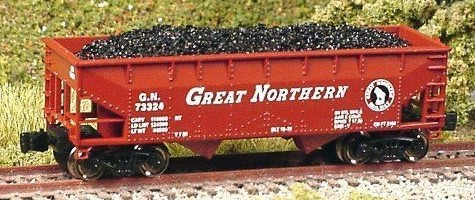

Specific Item Information: Road Numbers: GN 73305 & 73324

Model Information: During the first half of the 20th Century, the most common carrier for the transport of coal via rail lines was, in fact, the pervasive little 50-55 ton, twin-bay hopper. Ever-inventive engineers designed a different style of this essential hauler which became enormously popular with many Railroads by the 1930s and 40s. This "offset-side" hopper car had a few advantages over the earlier "rib-side" type. The crease in the upper sides led to more structural strength without using heavier materials, and there was a greater rated capacity with the side panels riveted to the outside of the ribbing, instead of being on the inside. The efficiency was a boon to the coal merchants! The concept proved successful, and was used to build ever-larger hoppers until after WW II, when "rivet pull-through" rendered it impractical for modern rotary dumping. Today, although they are seen less frequently, offset-side hoppers remain an important part of railroad history. Full Throttle presents a universal model of these unique hoppers.

Prototype History: The late 1920s saw the introduction of the AAR standard “offset-side” 50- and 70-ton hoppers. The design went through several variations in the late 1920s and early 1930s before settling on two versions of the 50-ton car and one 3-bay, 70-ton car in 1935. Most roads went for the AAR standard designs, but the N&W, VGN, and Pennsy were notable holdouts. World War II brought the famous “war emergency” hoppers (only the N&W and MP bought the 70-ton version) and several composite versions of existing designs. After the war, AC&F found some brief success with a welded outside-stake hopper design, but the weld joints broke under the stress of loading and unloading rather than flexing like riveted joints. The offset-side design also had problems: the inside stakes were more prone to corrosion, and they suffered worse from loading and unloading stress than outside-staked hoppers. The design waned in the 1950s and was all but abandoned for new cars by 1960. Some roads (notably the C&O, the B&O, and the L&N) made the best of a bad situation by rebuilding their offset-side cars with all new outside-staked sides in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Road Name History: The Great Northern was born in 1881 with the consolidation of several railroads of the northern plains under the leadership of James J. Hill. By 1893, the mainline from the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River to Seattle was complete.

The GN had two distinctly different characters. The eastern half was a largely flat, grain producing region serving cities like Fargo, the Twin Cities, Grand Forks, Duluth, Sioux Falls, Sioux City and even Winnipeg in Canada. The east end also included the iron ore rich regions of Minnesota. Half of North Dakota was blanketed by GN branchlines (21 in all) serving every imaginable grain elevator.

The western half is the mountainous portion that most people identify with Great Northern. This included crossing the northern Rockies and the even more difficult Cascade ranges. Cities on the western half included Billings, Butte, Helena, Havre, Spokane, Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver. In 1931, a connection to the Western Pacific was completed from Bieber north to Bend, Oregon. This line was disconnected from the rest of the Great Northern. They used trackage rights on the Oregon Trunk and SP&S to bridge the gap. The Cascade Tunnel, the longest on the continent at 7.8 miles, wasn’t completed until 1931. Construction included a massive sluiceway and hydro-electric power station to feed the electrified line through the tunnel and several miles of railroad on either side. This replaced the original Cascade Tunnel which was a third as long but 500 feet higher up the mountain. That replaced the original route that was another 700 feet higher, had 4% grades and 50 miles of snowsheds. All told, Great Northern had about 8,300 route miles.

The steam era was especially unkind to the Great Northern. They seemed to go out of their way to make their locomotives ugly. Belpaire fire boxes were the norm (made famous by the Pennsylvania, made hideous on the GN.) Headlights were often mounted just above center giving them a spinster look. Cab fronts were often at odd angles. The tender coal bunkers were often taller than the engines. But it wasn’t just aesthetics. GN had a knack for buying the wrong engines for the job. 150 Prarie type 2-6-2’s were so unstable at speed that they were busted down to branchline duty almost straight away and none survived after about 1930. Their first 4-8-2 Mountains built for passenger and fast freight were such a disaster, they were rebuilt into 2-10-2’s. Many railroads had built Mountains out of Mikes but no one had ever started with a Mountain and had to build something else from it. The first 2-6-6-2’s were so under-powered, the boilers were used to make Mikados instead. They did manage to build the largest, fastest, and most powerful Mikados in the country however. Their articulated fleet included 2-6-6-2, 2-6-8-0 (later rebuilt into Mikes), 2-8-8-0, 2-8-8-2 types as well as a pair of Challengers originally delivered to SP&S. Many engines were dressed up with green boilers and boxcar red cab roofs.

For the first generation of diesels, GN bought like many large railroads did: a sampling from everyone. Cab and hood units from EMD and Alco and switchers from EMD, Alco, and Baldwin populated the roster. GN’s first generation geeps and SD’s were delivered with the long hood as the front. This included their GP20’s which had high short hoods and the long hood as the front. Aside from an early black scheme for switchers, the GN fleet was delivered in Omaha Orange and green with yellow piping.

Beginning with the arrival of GP30s in 1962, the paint scheme was simplified by dropping the bottom orange band and the yellow piping. For the second generation, General Electric replaced Alco as a supplier of new road engines.

In 1962, some GN freight cars began to appear in Glacier Green which ran along side the vermilion paint adopted in 1956. In 1967, they went for a major shift. Sky Blue, white, and dark gray were joined by a new version of the Rocky the goat logo. There was talk that this would become the paint scheme for Burlington Northern. The GN name and logo was painted on a steel panel bolted the the hand railings of hood units, making it easier to remove after the merger. For whatever reason, they went with green, black and white, a version of which was simultaneously being tested on the Burlington Route. In 1970, Great Northern, Northern Pacific, Spokane Portland & Seattle, and Burlington Route merged to form Burlington Northern.

The GN had two distinctly different characters. The eastern half was a largely flat, grain producing region serving cities like Fargo, the Twin Cities, Grand Forks, Duluth, Sioux Falls, Sioux City and even Winnipeg in Canada. The east end also included the iron ore rich regions of Minnesota. Half of North Dakota was blanketed by GN branchlines (21 in all) serving every imaginable grain elevator.

The western half is the mountainous portion that most people identify with Great Northern. This included crossing the northern Rockies and the even more difficult Cascade ranges. Cities on the western half included Billings, Butte, Helena, Havre, Spokane, Portland, Seattle, and Vancouver. In 1931, a connection to the Western Pacific was completed from Bieber north to Bend, Oregon. This line was disconnected from the rest of the Great Northern. They used trackage rights on the Oregon Trunk and SP&S to bridge the gap. The Cascade Tunnel, the longest on the continent at 7.8 miles, wasn’t completed until 1931. Construction included a massive sluiceway and hydro-electric power station to feed the electrified line through the tunnel and several miles of railroad on either side. This replaced the original Cascade Tunnel which was a third as long but 500 feet higher up the mountain. That replaced the original route that was another 700 feet higher, had 4% grades and 50 miles of snowsheds. All told, Great Northern had about 8,300 route miles.

The steam era was especially unkind to the Great Northern. They seemed to go out of their way to make their locomotives ugly. Belpaire fire boxes were the norm (made famous by the Pennsylvania, made hideous on the GN.) Headlights were often mounted just above center giving them a spinster look. Cab fronts were often at odd angles. The tender coal bunkers were often taller than the engines. But it wasn’t just aesthetics. GN had a knack for buying the wrong engines for the job. 150 Prarie type 2-6-2’s were so unstable at speed that they were busted down to branchline duty almost straight away and none survived after about 1930. Their first 4-8-2 Mountains built for passenger and fast freight were such a disaster, they were rebuilt into 2-10-2’s. Many railroads had built Mountains out of Mikes but no one had ever started with a Mountain and had to build something else from it. The first 2-6-6-2’s were so under-powered, the boilers were used to make Mikados instead. They did manage to build the largest, fastest, and most powerful Mikados in the country however. Their articulated fleet included 2-6-6-2, 2-6-8-0 (later rebuilt into Mikes), 2-8-8-0, 2-8-8-2 types as well as a pair of Challengers originally delivered to SP&S. Many engines were dressed up with green boilers and boxcar red cab roofs.

For the first generation of diesels, GN bought like many large railroads did: a sampling from everyone. Cab and hood units from EMD and Alco and switchers from EMD, Alco, and Baldwin populated the roster. GN’s first generation geeps and SD’s were delivered with the long hood as the front. This included their GP20’s which had high short hoods and the long hood as the front. Aside from an early black scheme for switchers, the GN fleet was delivered in Omaha Orange and green with yellow piping.

Beginning with the arrival of GP30s in 1962, the paint scheme was simplified by dropping the bottom orange band and the yellow piping. For the second generation, General Electric replaced Alco as a supplier of new road engines.

In 1962, some GN freight cars began to appear in Glacier Green which ran along side the vermilion paint adopted in 1956. In 1967, they went for a major shift. Sky Blue, white, and dark gray were joined by a new version of the Rocky the goat logo. There was talk that this would become the paint scheme for Burlington Northern. The GN name and logo was painted on a steel panel bolted the the hand railings of hood units, making it easier to remove after the merger. For whatever reason, they went with green, black and white, a version of which was simultaneously being tested on the Burlington Route. In 1970, Great Northern, Northern Pacific, Spokane Portland & Seattle, and Burlington Route merged to form Burlington Northern.

Brand/Importer Information: Greetings, I'm Will, a Fine Arts graduate of Kutztown University in Pennsylvania who grew up in the Delaware Valley. I worked for 30 years with the Pennsylvania German Folklife Society. For ten years I had a permanent booth, each month showing my "PA Dutch" wares, at the country's largest under-roof Antique Market in Atlanta, GA. When Mom and Dad started to have health issues, I was forced to give up the nomadic life, but during my travels I came to love Z Scale Model Railroading, as I could easily take small layouts with me to the motels and play with my trains in the evenings!

Now that Mom and Dad are gone, and after many years of providing care for my "Pappy" in Florida, I find myself a homebody in the "Sunshine State" with a neat little business, supplying interested Z hobbyists with rolling stock and unique quality products!

Item created by: CNW400 on 2021-08-25 12:51:24. Last edited by CNW400 on 2021-08-25 12:51:59

If you see errors or missing data in this entry, please feel free to log in and edit it. Anyone with a Gmail account can log in instantly.

If you see errors or missing data in this entry, please feel free to log in and edit it. Anyone with a Gmail account can log in instantly.