Athearn Trains 36-Foot Old Time Stock Car

Published: 2023-02-15 - By: CNW400

Last updated on: 2023-02-02

Last updated on: 2023-02-02

visibility: Public - Headline

Road Names and Pricing

Released in October 2022, Athearn Model Trains expanded their 36-foot Old Time Stockcar collection with seven paint schemes. Originally announced in August 2021, these fully assembled models were produced from MDC/Roundhouse tooling acquired by the Athearn Trains parent company, Horizon Hobby, in 2005. The road names included in the recent series are:- Canada Cattle Car Company

- Canadian National

- Cotton Belt

- Rock Island

- Santa Fe

- St. Louis Iron Mountain & Southern

- Union Pacific

Prototype History

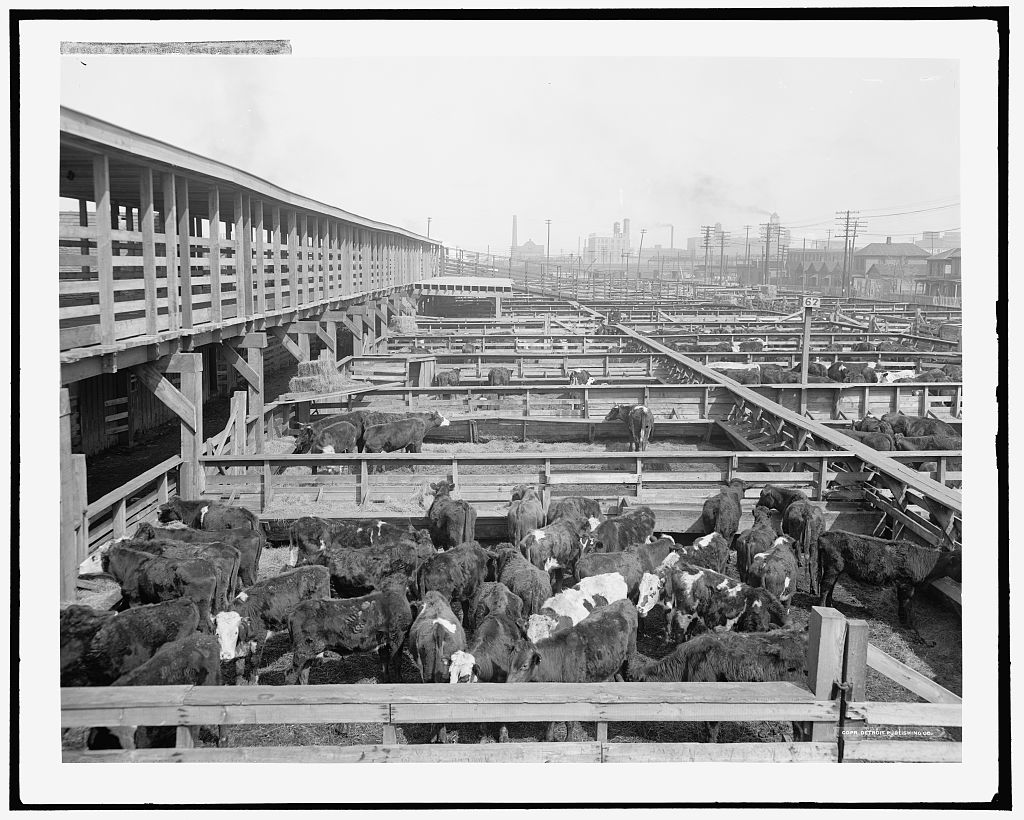

In 1870, the beginnings of a stock yard were constructed on five acres of land directly west of downtown Kansas City, Missouri in an area known as West Bottoms. The West Bottoms district is in both Kanas City, Missouri and Kansas City, Kansas and sits at the convergence of the Missouri and Kansas Rivers. The location on the waterfronts established access to supplies and resources and created commerce shipping routes. The intention of the stockyards was to provide a more attractive network for livestock owners situated west of Kansas City – more opportunity to market and sell at fair prices to the highest bidder.

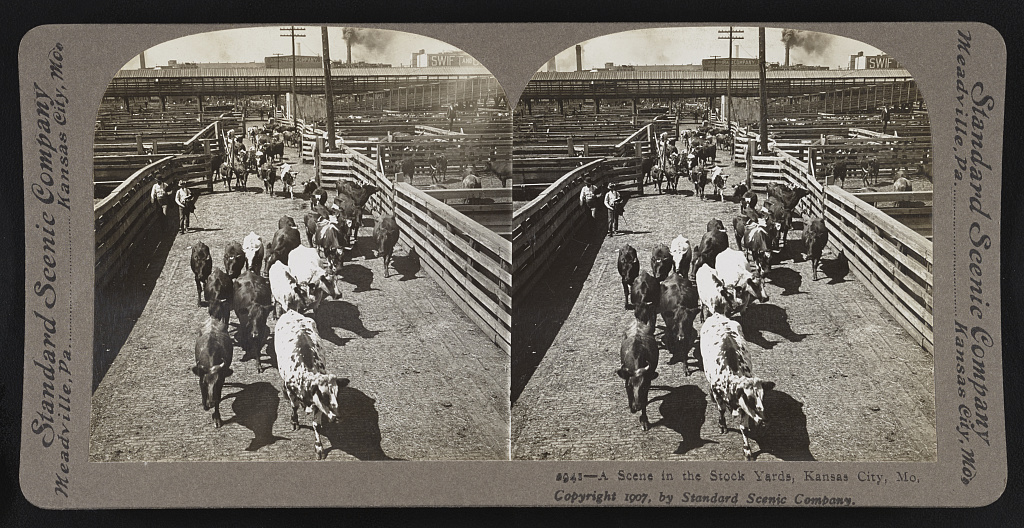

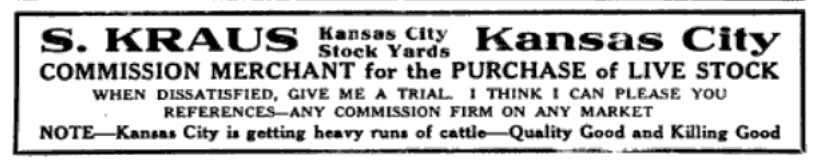

Now grown to 13 acres, the Kansas City Stockyard Company was officially established with railroad connections to the Kansas Pacific and Missouri Pacific tracks. The growth of the railroads expedited the movement of livestock from the western grasslands of Kansas, Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas to a central market in Kansas City. At its peak during the 1920s, over ten miles of track were inside the expanded 207-acre stockyards with 16 railroads shipping product to 42 states. The stockyards and railroads created a national market for the livestock of the west and southwest with meatpacker giants building facilities in Kansas City – including both Chicago meat industry moguls Philip Armour and Gustavus Swift in the 1880s. With 10s of thousands of livestock arriving daily by either rail or cattle drovers – somebody was needed to care of the animals, to classify and separate the livestock into different groupings based on breed, weight, and quality of meat, to know WHO to sell to and WHAT was the current fair market value. These people became to be known as the Kansas City Livestock Commission Merchant.

“Kansas City Livestock Commission Merchant is one who receives, sells or buys livestock and charges a commission for the same” - Kansas City Livestock Exchange

By 1890, the Livestock Commission Merchant (LCM) had become the main middleman of the livestock trade which included cattle, hogs, and sheep with a separate market for horses and mules. The LCM facilitated the sale of livestock for a commission fee. The reasonable commission rate was the same from 1886 to 1921:

- 50-cents for each head of cattle

- 10-cents for each head of hog or sheep

With advances in rail stockcar design the commission schedule was simplified to:

- $12 per stockcar of cattle (on average 20-24 heads of range cattle / 17-19 heads of corn fed)

- $10 per stockcar of calves or yearlings

- $6 per single-deck railcar of hog or sheep

- $10 per double-deck car of hog or sheep

Unlike cattle drovers, the LCM did not take title of the animals – any risk of illness or injury to the animals was the responsibility of the livestock owner and the transporting railroad. It was not uncommon for a train to arrive with many dead, crippled and/or ill animals aboard. Once the animals reached the stockyards, the railcars were unloaded, and the animals were allocated to pens based on breed classifications, weight, and quality. The consigned Livestock Commission Merchant firm watered, fed, and cleaned the animals. Each morning buyers walked the catwalks above the pens, selected their stock and struck an oral deal with the LCM.

The Livestock Commission Merchant firms not only provided services in Kansas City, but hired hands called solicitors traveled considerable distances to locate and influence ranchers to consign with a particular firm. These solicitors also provided advice and gave current market quotes with price information from the Kansas City, St. Louis, Chicago, and Omaha markets – thanks to the telegraph systems.

This cooperation between the stockyard and railroads replaced the function of cattle drovers (cowboys) that could only handle a few thousand cattle head and took months to drive the herd to market. Conversely, in 1883 a freight train could travel from Denver to Kansas City in 28 hours and to Chicago within 3 days. The quick trip to market reduced the amount of ‘shrinkage’ experienced by the animals and allowed livestock owners to take immediate advantage of the market when demand was high. Additionally, drovers tended to ignore sheep and hogs and these markets were only local until the railroads allowed these farmers to benefit from a national market at the stockyards of Kansas City, Chicago, and St. Louis. Lastly, with over 300 Livestock Commission Merchant firms active during the heyday of Kansas City Stockyards, the LCM companies had a great deal of influence in the bank sector. The LCM firms were able to procure advances on consigned livestock – thus providing a source of loans for farmers and ranchers...something the cattle drover could not provide.

This movement of livestock across regions created a dilemma – the spread of disease. Initially a local issue became a national crisis as outbreaks of Texas fever, pleuro-pneumonia, hog cholera, and tuberculosis spread throughout the markets in Kansas City and Chicago. In 1884 the Federal Government responded with the formation of the Animal Industry Bureau which were granted the powers to identify and destroy any diseased animal and to quarantine a stockyard which had become infected.

As with any successful business venture, corrupt individuals will take advantage of others for their own gain. Some unethical practices amongst the Commission Merchants included defrauding the participants of the transaction since most of the deal relied on the ‘honor system’ and oral negotiations. Also, speculative purchasing by the LCM firms – buying livestock on their accounts with the anticipation of higher prices in the near future. Finally, firms offering rebates or commission rates below operating costs to ensure consignments and eradicate competition.

These unscrupulous business procedures and a 1919 Federal Trade Commission (FTC) report of packers manipulating the free market by restricting the flow of foods and controlling the price of meats lead to the passing of the Packers and Stockyards Act of 1921. President Warren Harding signed the Act into law on August 15, 1921, with the intention to "regulate interstate and foreign commerce in livestock, livestock produce, dairy products, poultry, poultry products, and eggs, and for other purposes."

The Act prohibited unfair and deceptive business practices, the restriction of supply, the manipulation of prices, conspiracy with others and the creation of a monopoly. Furthermore, the law demands that every employee of a commission firm must register with the government, the commission firm must deliver payment to the owner of livestock promptly, must maintain accurate scales (tested for accuracy at least twice annually) and certify all weights as accurate, maintain adequate business records, file annual reports, and permit inspection of all records and business facilities by the Secretary of Agriculture.

After the passage of this Act, the ‘Big Five’ (Armour, Cudahy, Morris, Swift, and Wilson) were forced to agree to a consent decree under the Sherman Antitrust Act which removed these packers from all non-meat production – including stockyards, warehouses, wholesale, and retail meat.

After World War II, the Kansas City Stockyards began a steady decline in business transactions. The Kansas City yards, now a distant memory, were once a mighty economic force – employing over 20,000 people with quarters for over 150,000 animals (70,000 cattle – 45,000 sheep – 40,000 hogs – 5,000 horse/mule). At its pinnacle, the Kansas City Stockyards accounted for 90% of the city’s industrial productivity and was America’s second largest meatpacking industry behind Chicago.

The improved national highway system and the trucking industry began to replace the railway system as a means of short haul livestock transport during the 1940s and 1950s. The packing industry started to become more local and drove business away from the Midwest plants with large livestock markets opening in Denver, Oklahoma City, Fort Worth, and Dodge City.

The Great Flood of 1951 delivered the greatest blow to the Kansas City Stockyards. Declared by President Truman as “one of the worst this country has ever suffered from water" - over 2,000,000 acres of land in Kansas and Missouri were flooded during June and July of that year. Heavy rains caused the swelling of the Kansas and Missouri Rivers – killing 17 and displacing over 500,000 citizens. Amongst other industries, the Kansas City Stockyards and Fairfax Airport were devastated. The West Bottoms area never fully recovered as meatpacking plants chose to rebuild elsewhere and a labor shortage developed with the uprooting of the population caused by the flood. The fate of the Livestock Commission Merchant was resolved when cattle future trading was adopted by the Chicago Mercantile Exchange in 1974 – the middleman was no longer needed.

The Kansas City Stockyards faced its demise in 1991. After over 120 years of service, the last cattle auction was held in September with the pens officially closing in October of that year.

The practice of transferring livestock in railcars dates to the 1830’s. The railroads sought to fill the need of transporting livestock from the North American farms and ranches to processing centers. The first type of rolling stock used was the common boxcar. The initial livestock routes were mostly short hauls, but the conditions of the boxcar were hardly ideal for the shipping of animals. The boxcar proved to be difficult to load and unload live animals. The boxcar also offered little stability for the livestock thus the trips took longer time because of the low speeds needed to prevent injury to the ‘cargo.’ This extra time meant loss of dollars to the railroads. Finally, the lack of fresh air and access to water was not ‘humane’ treatment of the animals - injury and death to the product was again profit slipping away from the shippers.

The railroads were reluctant to invest heavily in the production of stock cars. First, stock cars were seen as single-use or limited-use specialty cars. Little revenue was realized beyond the hauling of animals. Secondly, the need for stock cars was seasonal, peaking during the fall months. Thus, much of the stock car fleet sat idle during the year.

The initial attempt to construct livestock specific cars was in 1870. Zadok Street designed the first patented stock car. Street’s creation included water troughs on the car floor and feed troughs extending down from the roof. The livestock cars ran on the 90-hour trip from New York City to Chicago – the design was inefficient as it could only hold six heads of cattle.

The 1880’s saw improvements to livestock railcars with innovations from the Mathers Stock Car and Burton Stock Car Companies - the designs were 28 or 32 feet long with a wood roof, wooden ends, and horizontal side-slants. The cars did not need to be pretty or weatherproof considering the cargo and did not need to be strongly constructed - the load never approached weight limitations. Railroads did try to keep animals strong and healthy by installing built-in feeders and water troughs and providing ample room for animals to recline. Nearly 78,000 stock cars were in railroad use by the turn of the 20th Century.

On June 29th, 1906, Congress approved The Animal Transportation Act to protect animals from cruel treatment while traveling long distances on the railroads. A similar Federal law was imposed in 1873 but was not strictly enforced. The Twenty-Eight Hour Law was created, in short, stating “that animals cannot be transported by rail carrier for more than 28 consecutive hours without being unloaded for five hours for rest, water and food.” There are some expectations to the rule and the law has been amended several times to stay current with changing technological advancements.

Railroads continued with the practice of either rebuilding or converting retired rolling stock and/or boxcars in need of repair into stock cars. These practices lead to a wide variety of styles and construction design on the rails. While most cars still had wooden ends, the use of retired boxcars with their steel Dreadnaught or Murphy ends created a host of different heights. Car heights varied between 8 feet to 10 1/2 feet.

Finally in 1930, the American Railway Association (ARA) purposed recommended designs for a stock car. These recommendations did not become the standard design and were not enforced by the ARA. The proposal included: 40-foot length with 40–50-ton capacity, steel underframe, wood ends, steel truss framing, slatted wood sides and a steel over wood roof.

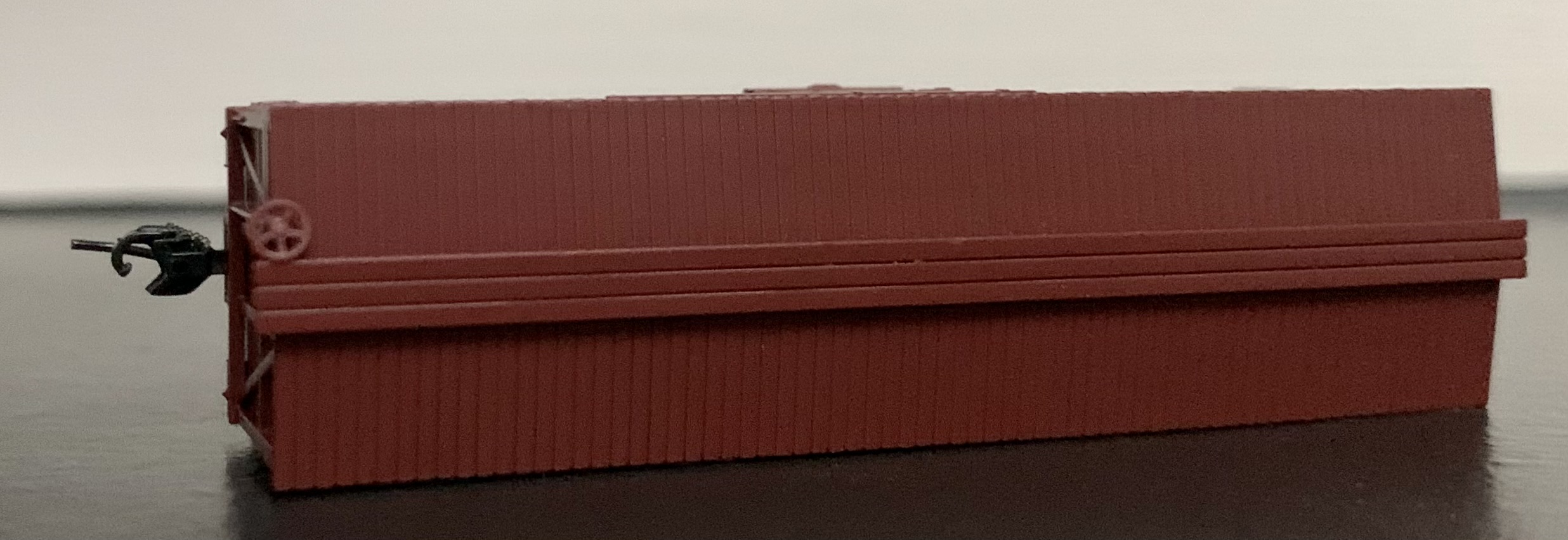

The Model

The ready-to-run 36-foot stockcar arrived in a clear plastic jewel case with a slip-off cover and a thick two-piece plastic cradle to support the model. The model information is clearly labeled on the end of the case for ease to locate when in storage. A thick plastic sleeve was wrapped around the car to protect the model from scuffmarks. No additional parts were found inside the case.The paint job is clean and even along the entire injection molded plastic model. The Santa Fe car is painted mineral brown with white lettering that is neat and legible. The Santa Fe name and logo never appeared on stock cars – dimensional data was stenciled on the bottom sill and reporting marks were usually painted on or above the drover doors. Furthermore, the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railway used the reporting marks A.T. & S.F. on stock cars until 1940 – switching to A.T.S.F. at that time. Athearn accurately followed these prototypical design elements on the Old-Time model which depicts a car built between 1890 to 1910. The stock car and livestock has been assigned to the S. Kraus Livestock Commission Merchant at the Kansas City Stockyards.

The sides feature a horizontal wood board configuration with a wooden sliding door and diagonal bracing. The near corner has one grab iron while the far corner has a full-length molded grab iron pattern to the car top – prototypical correct. A stirrup step is also located near each corner. The intricately detailed truss rod and turnbuckle system is visible at side views. Truss-rods supported freight car underframes on early wood and steel frame railcars – furnishing reinforcement to reduce warpage and sagging. The rods extend from one end sill to the other with turnbuckles to adjust tension. A queen post design had a single turnbuckle while a king post design sported two turnbuckles per rod. A familiar modern use of this system is the truss-rod support for a guitar neck.

Both ends of the stock car display a horizontal wood plank pattern with additional diagonal bracing. The B-end features a separately applied vertical stem-winder hand brake, brake rod and small brakeman platform. The A-end has a small drover door – allowing access to the stock car without opening the large sliding doors. The road number is centered on both ends on the top panel – prototype correct according to Santa Fe references.

The top of the stockcar features a wood plank roof and a separately applied full-length roof walk. The underside displays a faux-wooden floor with molded plastic truss rod, turnbuckle, and brake cylinder details. The railcar rides along screw mounted Athearn arch bar trucks and blackened silver metal wheels.

The arch bar was the most predominate truck used during the 1890s through 1910s – pressed steel components held together by bolts that tended to loosen with the wear-n-tear of carrying 40- and 50-ton capacity cars at faster speeds and longer distances. The railroad industry originally banned the use of arch bar trucks from interchange duty starting on January 1, 1938, but that date was postponed until 1941 with the nation climbing out of the Great Depression. Arch bar trucks were still a common sight on freight cars into the 1960s on those assigned to online service only.

The car is 2 3⁄4 inches in length and weighs 0.9 ounces, which is perfect according to the National Model Railroad Association (NMRA) recommendations of 0.93 ounces for a car this size. I found it an excellent runner while testing on Kato Unitrack with zero issues around curves or through turnouts at slow and medium speeds. Both body-mounted McHenry magnetically operated knuckle couplers were affixed to proper heights. The recommended minimum operating radius is 9 3⁄4".

Although not the sexiest piece of rolling stock, I have a soft spot for livestock cars...the look and smell of these cars symbolize the gritty, dirty work of the early railroad and the growth of Midwestern America. Athearn has faithfully reproduced an early version of these railcars. Sturdy construction with perfect weight and metal wheels makes an excellent runner. Prototypical design and stencil work – intricate underside truss rod details. Not much to complain about – maybe an operational sliding door for that $35 price tag? So go grab your rubber boots and shovel and put a few of these Athearn 36-foot Stock Cars on your layout.

Photo Credits

1. Stock yards, Kansas City, Mo. Detroit Publishing Co., Copyright Claimant, and Publisher Detroit Publishing Co. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress,2. A scene in the stock yards, Kansas City, Mo. (1907). [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2018650110/. No known restrictions on publication.

3. Cattle merchants in stockyards. Kansas City, Kansas. Rothstein, Arthur, photographer. May 1936. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress,

4. Stock yards, Kansas City, Mo., (1905) [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2018650111/. No known restrictions on publication.

5. Loading pens for livestock to be shipped in freight cars. Union Stockyards, South Omaha, Nebraska. Wolcott, Marion Post, 1910-1990, photographer. Farm Security Administration - Office of War Information Photograph Collection (Library of Congress). No known restrictions.

6. Scanned Image – The National Provisioner August 25, 1917, Page 48