Athearn 36-Foot Old Time Wood Boxcar

Published: 2022-08-15 - By: CNW400

Last updated on: 2022-08-10

Last updated on: 2022-08-10

visibility: Public - Headline

Released in March 2022, Athearn Model Trains expanded their 36-foot Old Time Wood Boxcar collection with six paint schemes. Originally announced in January 2021, these fully assembled models were produced from MDC/Roundhouse tooling acquired by the Athearn Trains parent company, Horizon Hobby, in 2005.

The pinnacle of 36-foot wooden boxcar construction lasted from 1890 to 1910 as it was then considered the standard length for a car – by 1910 railroads began to transition to 40-foot cars. Many 36-foot cars lasted in revenue freight service well into the 1950s with rebuilt steel underframes. The typical 36-foot boxcar was 8 ½-feet tall with a hauling capacity of 40-tons (80,000 pounds). The 10-foot-tall boxcar was not introduced until 1936.

Although these freight cars had a large capacity of 40-tons, many ran as LCL or ‘Less-Than-Carload' shipments. LCL cargo was limited in size and did not require an entire boxcar. Every town throughout North America had a nearby freight house that delivered and shipped mail, packages, goods, equipment, etc. inside these less than full boxcars. The early wooden boxcars featured some unique characteristics since as truss-rods, arch bar trucks, multiple roof designs and advanced coupling systems.

Truss-rods supported freight car underframes on early wood and steel frame railcars – furnishing reinforcement to reduce warpage and sagging. The rods extend from one end sill to the other with turnbuckles to adjust tension. A queen post design had a single turnbuckle while a king post design sported two turnbuckles per rod. A familiar modern use of this system is the truss-rod support for a guitar neck.

The arch bar was the most predominate truck used during the 1890s thru 1910s – pressed steel components held together by bolts that tended to loosen with the wear-n-tear of carrying 40- and 50-ton capacity cars at faster speeds and longer distances. The railroad industry originally banned the use of arch bar trucks from interchange duty starting on January 1, 1938, but that date was postponed until 1941 with the country climbing out of the Great Depression. Arch bar trucks were still a common sight on freight cars into the 1960s on those assigned to online service only.

At the outset of the 20th century, rolling stock used four varieties of roofs: 1. Tongue-n-groove double layer of wood boards, 2. Interior layer of wooden boards sheathed with metal panels, 3. Interior layer of sheet metal covered with wood, and 4. Double layer of wood boards separated with tarpaper or felt canvas between them. Brakemen preferred wooden surfaces over metal for greater foot traction and wood roofs withstood the ravages of railroad activity better than sheet metal.

Lastly, the expanding railroad industry was facing a dilemma with over forty different coupler designs in use by the 1880s – many of these configurations were not compatible. This predicament caused the Master Car Builders Association (MCB) to intercede and adopt a single standard coupling system. The Master Car Builders Association was created in 1867 to resolve troubles caused by the interchanging of freight cars. The MCB later reorganized into the Association of American Railroads (AAR).

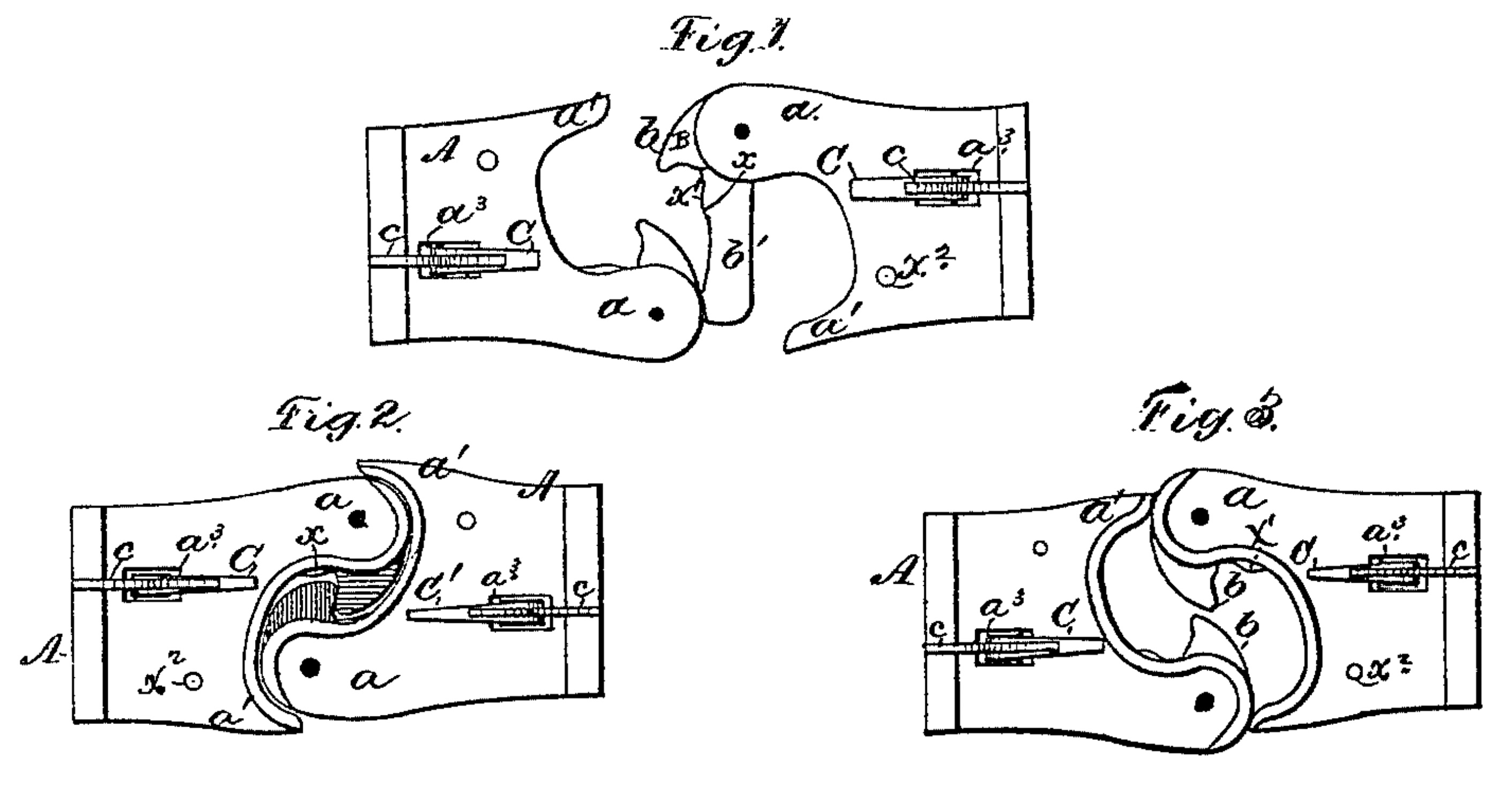

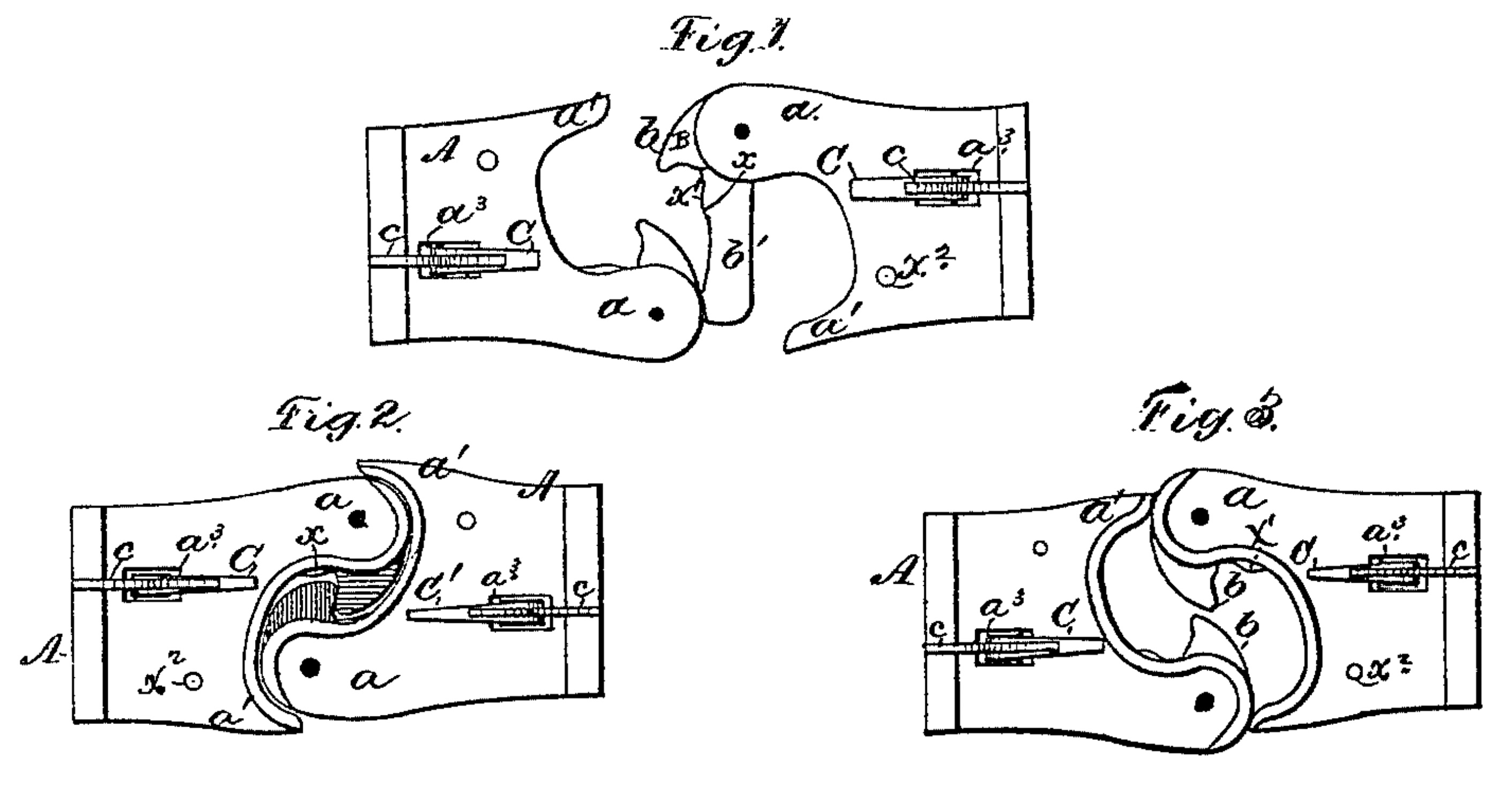

After comprehensive testing and research, the Janney-type coupler system was adopted as the industry standard. Eli H. Janney developed his semi-automatic knuckle coupler in 1873 (U.S. Patent 138,405). The Janney couplers linked on contact, thus eliminating the need to manually conjoin cars together. Furthermore, the Janney-type coupler successfully hooked-up with link and pin systems until they were phased-out in North America.

Diagram of the Janney Coupler – Eli H. Janney / April 1, 1873 (U.S. Patent 138,405)

This media file is in the public domain in the United States. This applies to U.S. works where the copyright has expired, often because its first publication occurred prior to January 1, 1927, and if not then due to lack of notice of renewal.

The paint job is clean and even along the entire injection molded plastic model. The Cotton Belt Route car is boxcar red with white lettering that is neat and for the most part legible. Some smaller characters are difficult to read – especially those stamped between the wood plank design.

The sides feature a vertical wood board configuration with a six-foot wooden sliding door. The near corner has one grab iron while the far corner has a full-length molded grab iron pattern to the car top – prototypical correct. A much too thick stirrup step in also located in each corner. The intricately detailed truss rod and turnbuckle system is visible at side views – adding a realistic perspective while admiring your train rolling along the tracks.

A large Cotton Belt Route logo is proudly displayed left of the sliding door. The St. Louis Southwestern Railway is a former Class 1 railroad that operated from 1891 to 1992 primarily in the states of Missouri, Arkansas, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Texas. Nicknamed ‘The Cotton Belt’ for their track rights in the southern regions where cotton was the predominant cash crop. The Cotton Belt Route was a subsidiary of the Southern Pacific Lines from 1932 until the Union Pacific Corporation acquired the Southern Pacific Transportation Company in 1996.

Stenciling standards were not enforced until the American Railway Association placed guidelines in 1925. With that noted, the data shared on the sides of early boxcars is erratic when comparing prototype images. On the Athearn Trains model, the reporting marks and road number are shown twice on each side profile. The car length (36-foot), capacity (80000 pounds), and coupler-type (MCB) are also displayed.

Other information reported is that the railcar is compliant with the United States Safety Appliance Standards. Enacted in 1893, the Federal Railroad Administration established laws relating to “safety appliances and equipment on railroad engines and cars, and protection of employees and travelers” (U.S. Department of Transportation Enforcement Manual).

Also stenciled right of the sliding door are the data lines: Minor Draft Gear (assembly behind the coupler the absorbs the energy from the pushing, pulling, and coupling of railcars), Yoke Attachment (the pocket for the draft gear that helps to maintain the gear in the correct position) and Metal Brake Beams (assist in minimizing uneven brake shoe wear and reduce the need for brake shoe replacement).

Both ends of the boxcar are wooden with a full-length molded grab iron composition on the left and a single grab iron on the right. The reporting marks and road number are neatly displayed in the upper right corner – the correct position according to prototype images. The brake-end features a separately applied vertical ‘stem-winder’ hand brake, brake rod and small brakeman platform. The brake wheel is mounted too short when compared to true-life photographs. The brake rod should be taller – the position of the wheel on the Athearn model would make it impossible to rotate in a real-life application. Either an error on Athearn’s part or an ingenious production idea to protect the brake wheel from being damaged.

The top of the boxcar features a wooden board roof and a separately applied full-length “wood” roof walk. The underside shows a wooden floor with molded plastic truss rod, turnbuckle, and brake cylinder details. The railcar rides along screw mounted Athearn arch bar trucks and blackened silver metal wheels.

The car is 2 ¾ inches in length and weighs 1.0 ounce, which is a tad heavy according to the National Model Railroad Association (NMRA) recommendations of 0.93 ounces for a car this size. I found it an excellent runner while testing on Kato Unitrack with zero issues around curves or through turnouts at slow and medium speeds. Both body-mounted McHenry magnetically operated knuckle couplers were affixed to proper heights. The recommended minimum operating radius is 9 ¾".

To see a list of all cars in this series, CLICK HERE

Road Names and Pricing

The road names represented in the most recent Old Time Boxcar selection include:- Chesapeake & Ohio (C&O)

- Cotton Belt Route (StL S-W)

- Missouri, Kansas & Texas (MKT)

- New York, Ontario & Western (NYO&W)

- Nickel Plate Road (NKP)

- Santa Fe (ATSF)

Prototype History

The boxcar emerged during the inception of the North American railroad. A basic superstructure affixed upon a flatcar or gondola with wooden frames, walls, and roof. The Mohawk & Hudson Railroad first experimented with the boxcar design in 1833 – housing their gondola loads during the harsh northeastern winters. With improvements to design, the steel frame 30-foot wood boxcar with a six-foot sliding door soon became the workhorse of the early railroad.The pinnacle of 36-foot wooden boxcar construction lasted from 1890 to 1910 as it was then considered the standard length for a car – by 1910 railroads began to transition to 40-foot cars. Many 36-foot cars lasted in revenue freight service well into the 1950s with rebuilt steel underframes. The typical 36-foot boxcar was 8 ½-feet tall with a hauling capacity of 40-tons (80,000 pounds). The 10-foot-tall boxcar was not introduced until 1936.

Although these freight cars had a large capacity of 40-tons, many ran as LCL or ‘Less-Than-Carload' shipments. LCL cargo was limited in size and did not require an entire boxcar. Every town throughout North America had a nearby freight house that delivered and shipped mail, packages, goods, equipment, etc. inside these less than full boxcars. The early wooden boxcars featured some unique characteristics since as truss-rods, arch bar trucks, multiple roof designs and advanced coupling systems.

Truss-rods supported freight car underframes on early wood and steel frame railcars – furnishing reinforcement to reduce warpage and sagging. The rods extend from one end sill to the other with turnbuckles to adjust tension. A queen post design had a single turnbuckle while a king post design sported two turnbuckles per rod. A familiar modern use of this system is the truss-rod support for a guitar neck.

The arch bar was the most predominate truck used during the 1890s thru 1910s – pressed steel components held together by bolts that tended to loosen with the wear-n-tear of carrying 40- and 50-ton capacity cars at faster speeds and longer distances. The railroad industry originally banned the use of arch bar trucks from interchange duty starting on January 1, 1938, but that date was postponed until 1941 with the country climbing out of the Great Depression. Arch bar trucks were still a common sight on freight cars into the 1960s on those assigned to online service only.

At the outset of the 20th century, rolling stock used four varieties of roofs: 1. Tongue-n-groove double layer of wood boards, 2. Interior layer of wooden boards sheathed with metal panels, 3. Interior layer of sheet metal covered with wood, and 4. Double layer of wood boards separated with tarpaper or felt canvas between them. Brakemen preferred wooden surfaces over metal for greater foot traction and wood roofs withstood the ravages of railroad activity better than sheet metal.

Lastly, the expanding railroad industry was facing a dilemma with over forty different coupler designs in use by the 1880s – many of these configurations were not compatible. This predicament caused the Master Car Builders Association (MCB) to intercede and adopt a single standard coupling system. The Master Car Builders Association was created in 1867 to resolve troubles caused by the interchanging of freight cars. The MCB later reorganized into the Association of American Railroads (AAR).

After comprehensive testing and research, the Janney-type coupler system was adopted as the industry standard. Eli H. Janney developed his semi-automatic knuckle coupler in 1873 (U.S. Patent 138,405). The Janney couplers linked on contact, thus eliminating the need to manually conjoin cars together. Furthermore, the Janney-type coupler successfully hooked-up with link and pin systems until they were phased-out in North America.

This media file is in the public domain in the United States. This applies to U.S. works where the copyright has expired, often because its first publication occurred prior to January 1, 1927, and if not then due to lack of notice of renewal.

The Model

The ready-to-run 36-foot wooden boxcar arrived in a clear plastic jewel case with a slip-off cover and a thick two-piece plastic cradle to support the model. The model information is clearly labeled on the end of the case for ease to locate when in storage. A thick plastic sleeve was wrapped around the car to protect the model from scuffmarks. No additional parts were found inside the case.The paint job is clean and even along the entire injection molded plastic model. The Cotton Belt Route car is boxcar red with white lettering that is neat and for the most part legible. Some smaller characters are difficult to read – especially those stamped between the wood plank design.

The sides feature a vertical wood board configuration with a six-foot wooden sliding door. The near corner has one grab iron while the far corner has a full-length molded grab iron pattern to the car top – prototypical correct. A much too thick stirrup step in also located in each corner. The intricately detailed truss rod and turnbuckle system is visible at side views – adding a realistic perspective while admiring your train rolling along the tracks.

A large Cotton Belt Route logo is proudly displayed left of the sliding door. The St. Louis Southwestern Railway is a former Class 1 railroad that operated from 1891 to 1992 primarily in the states of Missouri, Arkansas, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Texas. Nicknamed ‘The Cotton Belt’ for their track rights in the southern regions where cotton was the predominant cash crop. The Cotton Belt Route was a subsidiary of the Southern Pacific Lines from 1932 until the Union Pacific Corporation acquired the Southern Pacific Transportation Company in 1996.

Stenciling standards were not enforced until the American Railway Association placed guidelines in 1925. With that noted, the data shared on the sides of early boxcars is erratic when comparing prototype images. On the Athearn Trains model, the reporting marks and road number are shown twice on each side profile. The car length (36-foot), capacity (80000 pounds), and coupler-type (MCB) are also displayed.

Other information reported is that the railcar is compliant with the United States Safety Appliance Standards. Enacted in 1893, the Federal Railroad Administration established laws relating to “safety appliances and equipment on railroad engines and cars, and protection of employees and travelers” (U.S. Department of Transportation Enforcement Manual).

Also stenciled right of the sliding door are the data lines: Minor Draft Gear (assembly behind the coupler the absorbs the energy from the pushing, pulling, and coupling of railcars), Yoke Attachment (the pocket for the draft gear that helps to maintain the gear in the correct position) and Metal Brake Beams (assist in minimizing uneven brake shoe wear and reduce the need for brake shoe replacement).

Both ends of the boxcar are wooden with a full-length molded grab iron composition on the left and a single grab iron on the right. The reporting marks and road number are neatly displayed in the upper right corner – the correct position according to prototype images. The brake-end features a separately applied vertical ‘stem-winder’ hand brake, brake rod and small brakeman platform. The brake wheel is mounted too short when compared to true-life photographs. The brake rod should be taller – the position of the wheel on the Athearn model would make it impossible to rotate in a real-life application. Either an error on Athearn’s part or an ingenious production idea to protect the brake wheel from being damaged.

The top of the boxcar features a wooden board roof and a separately applied full-length “wood” roof walk. The underside shows a wooden floor with molded plastic truss rod, turnbuckle, and brake cylinder details. The railcar rides along screw mounted Athearn arch bar trucks and blackened silver metal wheels.

The car is 2 ¾ inches in length and weighs 1.0 ounce, which is a tad heavy according to the National Model Railroad Association (NMRA) recommendations of 0.93 ounces for a car this size. I found it an excellent runner while testing on Kato Unitrack with zero issues around curves or through turnouts at slow and medium speeds. Both body-mounted McHenry magnetically operated knuckle couplers were affixed to proper heights. The recommended minimum operating radius is 9 ¾".

Conclusions

Another solid release from Athearn Trains...filling the need for those modelers that recreate the early days of the North American railroad. Sturdy, no frills construction – much like that real thing. Exemplary underside truss rod and turn buckle detail, metal wheels and body mounted couplers score big points. If I were to nitpick for some negative comments: unattractive molded grab irons, unclear stamping along panel lines, and hand brake stem too short. But I would be a cranky ‘old-timer’ to complain much about those faults. In short – grab a few of these and relive the days when steam ruled the landscape.To see a list of all cars in this series, CLICK HERE