Atlas Model Railroad 70-Ton Ore Car

Published: 2022-07-15 - By: CNW400

Last updated on: 2022-07-15

Last updated on: 2022-07-15

visibility: Public - Headline

Atlas Model Railroad 70-Ton Ore Car

During the summer of 2021, Atlas Model Railroad expanded their 70-ton Ore Hopper Car collection. First offered by Atlas in 1969, ore cars or ‘jennies’ were specially designed railcars built to haul the heavy, dense deposits of iron ore – from mine to ship and from ship to mill.Road Names and Pricing

The most recent Trainman release includes six different paint schemes. The road names represented in this collection include:- Canadian National

- Canadian Pacific (CP Rail)

- Duluth, Missabe & Iron Range

- Great Northern

- Milwaukee Road

- Union Pacific

Prototype History

Iron ore: a mineral or rock rich in iron oxide. The metallic properties of this ore can be extracted and used as the main component in steel production – 98% of mined iron ore is utilized in steel fabrication. Over 50 countries mine iron ore with Australia and Brazil together accounting for about 2/3 of the world’s total exports.During the 1880’s vast amounts of iron ore deposits were discovered in the northeast region of Minnesota – from Duluth to the United States-Canadian border. The largest diggable deposit of hematite ore in the world – the Mesabi Range and Vermillion Range being the two primary locations. The ore mines were located 70 miles inland from Lake Superior and a mode of transportation was needed to haul the heavy cargo to the water docks for shipment to the steel mills.

The Duluth & Iron Range Railroad was constructed to service the Vermillion Range with the first ore carloads hauled in July 1884. The Duluth, Missabe & Northern Railroad was to handle the mines of the Mesabi Range with the first train placed into service in October 1892. In 1901, U.S. Steel acquired control of both railroads – operating each separately until merging them together in 1938 to form the Duluth, Missabe & Iron Range Railway (DM&IR). Known as the Missabe Road, the railroad operated in northern Minnesota and Wisconsin carrying iron ore and taconite to Lake Superior shipping ports. The Canadian National (CN) acquired controlling interest of the railroad in May 2004 and merged the Duluth, Missabe & Iron Range Railway into the CN owned Wisconsin Central Ltd in December 2011.

Hematite is a magnetic rock with an iron content up to 70%. Hematite fluctuates in color from red to rust brown and derives its name from the Greek word for blood protein – hemoglobin. Ores containing high concentrations of hematite or magnetite (greater than 60% iron) are termed ‘direct-shipping ore’ or ‘natural ore’ and are fed straight into blast furnaces.

Iron ore cars, nicknamed “jennies”, are a specialized type of hopper railcars manufactured to exclusively transport iron ore. Iron ore is much heavier and denser than coal – iron ore weighs approximately 155 pounds per cubic foot while coal weighs about 80 pounds per cubic foot. Thus, a standard size hopper would only be partially filled before reaching its weight limit. The smaller ore car filled to capacity would carry the same weight as the half-filled standard open hopper. The first recorded use of ore cars was in the upper Michigan region at the Maquette Range in the mid-1840s.

The initial ore cars were short, four-wheel wooden structures that hauled 10-15 tons. These cars transformed into an eight-wheel car in the 1880s that could ship 20-25 tons of iron ore. The turn-of-the-century saw the dawn of the 50-ton ore car...wood sides with steel posts and underframes. These cars had a ‘boxy’ appearance with tall sides, and some were used in service until the mid-1940s. During the 1910s, the ore hopper was amongst the earliest all-steel cars – built to withstand the abuse of loading and unloading heavy cargo.

The standard length of an ore car is 24-feet long to match the size of ore dock unloading pockets. Ships were found to be the most efficient means to transport the heavy ore cargo. The railroads hauled the iron ore to the Lake Superior shipping ports on the shores of Minnesota and Michigan. Ships at these ports used the Great Lakes to transport the raw iron ore to the steel mills in such areas as Chicago, Pittsburgh, upper Ohio, and western New York state.

Batches of ore cars are moved onto tracks above shipping docks. The docks run perpendicular to the shore to allow loading on either side. The rail unloading area, most commonly, is four tracks wide – running the length of the dock with two sets of track pockets serving either side. The length of these ore docks are between 1200-2300 feet long, 65-85 feet tall and 52-65 feet wide. Early docks were constructed with timber with the first steel and concrete dock built in 1909 by the Duluth & Iron Range.

The cars bottom-dump their load into a series of 12-foot-long bins or pockets located below the tracks. Chutes extend from these pockets and reach the ship’s cargo hatches and the loose iron ore pours onboard. The ore dock employee, called a loader, operates the chutes under the direction of the ship’s crew to assure proper balance of the vessel.

Although load capacity increased over the years from 50 to 70 to 100-tons, the length of the ore railcar remained the same (24-feet). The later steel cars were constructed with taller sides, deeper pockets, or wider bodies.

Iron ore is surfaced mined: open-pit mining which clears away the overlying soil and rock to expose the material to be removed. After the iron ore has been extracted with heavy construction equipment – the material is separated by type, iron content, and flow rate (fine or coarse). The divided iron ore is loaded onto a single purpose railcar with a gravity bottom unloading door.

The centered dump door was operated in early cars with a side-mounted wheel that was cranked by hand to open and close. In 1910, the Association of American Railroads (AAR) approved a standard unloading design with gears behind the exterior posts that drove the door mechanisms. These gears were activated with a wheel inserted in a square control post. In the 1940’s a power wrench mounted on a cart was wheeled car to car to open the bottom door.

The Association of American Railroads designated the ore car as a Class ‘H’ Hopper Car Type HMA: “Open top, self-clearing car having fixed sides and ends, and bottom consisting of two divided hoppers with doors hinged crosswise of car and dumping between rails.” The ore dock employee in charge of opening and closing the bottom outlet doors was called a ‘trapper’. A ‘dumper’ cleared the hopper with long steel poles called ore punchers. The steel pipes punched/poked compressed piles or banged on the sides of the car to free any cargo clinging to the interior walls of the hopper. The ‘dumper’ was also assigned the job of clearing-out ‘flat-top’ loads – wet loads of iron ore that turned into a thick mud (sometimes taking hours to unload a single car). The role of the ‘dumper’ was eventually replaced with mechanical car shakers.

Furthermore, if a load was delivered to the dock frozen together, the icy iron ore was thawed with steam from a locomotive parked on an adjacent track. The ore car has holes located near the four corners was swinging door covers. Pipe extensions from the locomotive are placed inside the hopper railcar holes and stream is forced into the ore car to melt the ice. An extremely dangerous job working in cold, slippery, and icy conditions with hot steam. The ore railroads stayed in contact with the National Weather Service to surmise if a steam crew was needed for the day or not. The Pennsylvania Railroad experimented was polyurethane foam insulation in the 1960s on their ore cars. Similarly, if the iron ore became frozen in the dock's storage bins, steam from a locomotive or hot water was poured into the pockets. This process of thawing was call slushing.

In 1957, infrared plants were introduced to thaw any frozen cargo. Ore cars with icy loads ran thru these plants to warm the raw iron ore. The warming buildings were widely used until the early-1970s when taconite (small pellets that did not freeze) replaced natural ore. More on taconite later.

With several railroads and manufacturers trying to enter the ore mining industry – there exists too many variations and configurations of rail equipment to give an in-depth analysis: the number and position of exterior posts, the height of the posts, smooth-side or ribbed, height & width of car, etc., etc., etc. In general, there were two categories of ore cars – the Minnesota car and the Michigan car.

Because the Michigan shipping docks had narrow track room, the ore cars built for the Michigan based ore facilities were slim in width (8’8” to 9’7”) but tall to have maximum load capacity (10’7” to 10’10”). In contrast the Minnesota car, working on largest dock trackage, was wider (10’5” to 10’9”) but shorter (10’3”) so not to exceed load weight limits. The Minnesota cars of the 1930s thru 1950s were the most popular ore cars ever produced with their familiar rectangular side panels, exterior post pattern and distinctive rivet lines.

Both versions of ore cars had a vertical-post brake wheel until the 1930s. In 1932, an end-mounted wheel and AB brakes became the standard on all new equipment. Furthermore, early ore cars rolled on arch bar trucks until being banned from interchange use in 1941. Railroads had already started the shift to cast-sideframe trucks in the 1930s with Vulcan and Andrews models being the most common until the switch to roller-bearing trucks in the 1950s.

The Milwaukee Road (the subject of my review) began to replace their fleet of 50-ton wooden ore cars with an order of 800 70-ton steel cars from the Pressed Steel Car Company built in 1928-1930. The new Milwaukee Road cars resembled the Minnesota-type ore hoppers in appearance (10’6” tall) but were narrower (9’4”) and had different exterior post bracing patterns. At the time, these were the only rectangular side panel cars working in the Midwest upper peninsula region.

The Pressed Steel Car Company was a manufacturer of rail equipment founded in 1899 with plant facilities in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and Joliet, Illinois. After diversifying into non-railroad products and renaming itself U.S. Industries, U.S. Steel acquired control of the company in 1956.

At the high point of the American iron industry – railroads of the upper Midwest managed their own shipping docks on the shores of the Great Lakes:

- DM&IR and Erie Mining in Duluth, Minnesota

- Great Northern in Allouez, Wisconsin

- Milwaukee Road and Chicago & North Western in Escanaba, Michigan

- Soo Line in Ashland, Wisconsin

- Northern Pacific in Superior, Wisconsin

- Lake Superior & Ishpeming in Marquette, Michigan

And how was the iron ore unloaded from the ship’s cargo hatches? The early days saw the use of diverse types of steam shovels, hoists, and buckets onboard ship – but this proved to be time-consuming, cumbersome, and dangerous with the need to maintain balance and equal weight distribution across the barge. Shoveling by hand was also implemented. That was until 1898 when George Hulett invented the Hulett ore unloader. The Hulett clamshell bucket extended over the edge of the ship and deposited large scoops into a larry car where it was weighed and then dumped into an ore railcar awaiting its trip to the steel mill. The Hulett bucket unloaded a ship within 10 hours - opposed to days for past methods. Modern ships are self-unloading with a series of conveyor belts extending from the cargo hatches into piles along the dockside.

Finally, back to taconite. Taconite pellets are made from raw iron ore through the process of pelletizing. Mining mills take large rock deposits of all grades of iron ore and grind them into a fine powder. The powder is then passed through a magnetic separator – capturing the iron products and disposing of the unwanted rock material. Water and bentonite (a key ingredient in kitty litter – acts as a binder) are mixed with the iron ore material to create a slurry. The excess water is filtered, and the slurry mixture is placed into a rolling drum – creating soft, squishy green balls. The green balls are baked into a hard pellet. The pellets go through a chemical change during the baking process and become non-magnetic. These process makes an easier material to handle during shipping and a superior end-product for the steel mills with most of the impurities removed.

Another benefit of taconite pellets is their weight - 130 pounds per cubic foot (about 30 pounds per cubic foot lighter than raw iron ore). This asset also created a new problem – existing ore cars were not being loaded to their maximum weight capacity with the lighter pellets filling-up the hoppers. Initially, the railroads added extension panels along the tops of the ore cars (similar to woodchip cars) to allow more product to be loaded onto the older ore cars. Then in the early 1970s, specialized 90-ton taconite hopper cars were built to haul these ore pellets.

Today, modern rotary dump and side-dumping gondolas are utilized alongside traditional ore hopper cars. Also, some older ore cars have been reassigned by the railroads to handle ballast or sand hauling service.

The Model

The ready-to-run hopper came packaged in a clear plastic jewel case with a slip-off cover and thin one-piece plastic cradle to support the ore car. The model information is printed on the end of the case to locate when in storage. A thin plastic sheet was wrapped around the car to protect the paint job from scratches. No extra detail parts were found in the case.

The Atlas Model Railroad Trainman collection is their economy line series – a low-cost, entry-level product without the bells and whistles. That business model is evident right away with the low-quality packaging.

Atlas originally released their ore hopper car assortment in 1969 – other that the improvements in the choice of wheels and couplers – not much has changed over the last 50-plus years.

Rumored to have been designed after a 1920s Bessemer and Lake Erie Railroad ore car – Atlas has fallen into the trap of many model manufacturers of using the same old tooling to represent all road name prototypes.

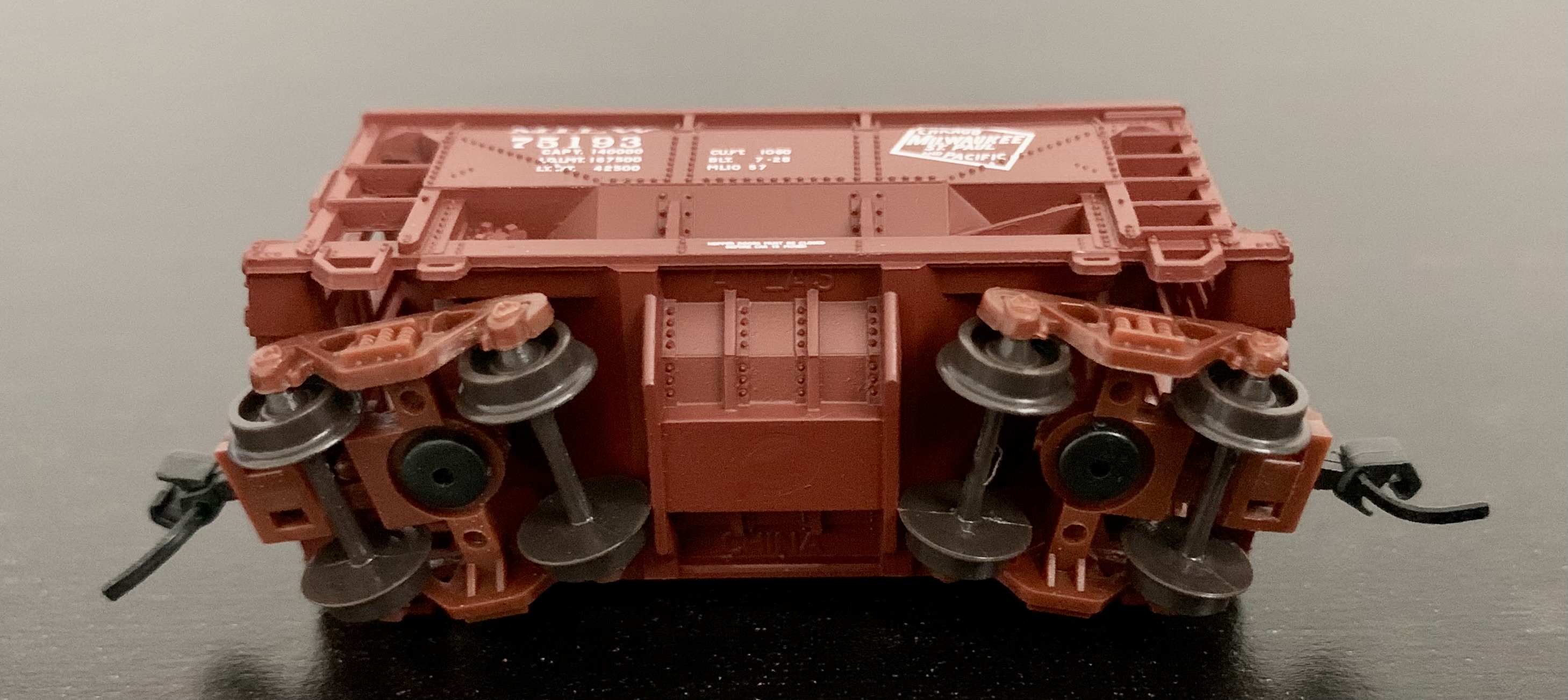

First, the paint job is clean and even along the entire injection molded plastic model. The Milwaukee Road ore car is painted boxcar red with white lettering. All lettering is sharp and crisp – even when magnification is needed for smaller print.

Secondly, the Atlas Model Railroad ore car does not truly represent a Milwaukee Road car based on all photographic evidence I was able to compile. The Milwaukee Road managed a rectangular-side ore car starting from 1928 until the railroad’s demise. Half of the rectangular-side panel extends the entire length of the car past the end platforms – appearing like a ‘smashed’ T-shape. Furthermore, the visible side panel does not angle in towards the top lip – it remains straight. In contrast, the Atlas Model is a generic version of an ore car with a thin portion of the side panel extending to the platform end with the top section slanting inwards at the lip. The grab irons and stirrup steps are also molded very thick. Lastly, I was not able to find any proof of the old Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul, and Pacific box logo being used on real life ore cars. Not saying they did not exist with this logo but all images I found either had ‘The Milwaukee Road’ spelled-out across the panels (photo from 1930) or the familiar ‘The Milwaukee Road’ slanted box logo stenciled on the side. Thus, a fantasy paint scheme from Atlas or a true-life logo that was covered by the Milwaukee Road shops without much visual recording.

Atlas does receive kudos for nice, sharp rivet-line detail and detailed brake gear and drop-door opening systems located behind the lower exterior posts.

Both ends feature a full-length ladder, support posts, crossover platform and working platform for the ‘dumper’ to clear-out the interior of the car during unloading. The 'B’ end has a separately applied high mounted brake wheel – the position of the brake wheel is period correct with the vertical post wheel phasing-out during this era.

A plastic iron ore load is included with the model – a unrealistic looking piece. Too plastic looking, too shiny, and too brown. If desired - the Atlas load can be either removed and replaced with a more authentic aftermarket product or left installed, used as a base, and glued with a natural material.

The underside is basic with a simple molded drop outlet door. The ore car rides along free-rolling trucks with brown plastic wheels and truck-mounted AccuMate couplers both aligned at proper heights.

The car measures 1 7/8 inches in length and weighs 0.5 ounces, which is light according to the National Model Railroad Association (NMRA) recommendations (0.79 ounces for this size car). Weight can be added once the plastic ore load is removed. However, I did find the ore car a good runner while testing on Kato Unitrack with no issues around curves or through turnouts at slow and medium speeds. I ran the car individually coupled to 40-foot boxcars at either end – I cannot personally speak about performance with a long string of ore cars hooked-up together.

Conclusions

If you are looking for an ore car to fulfill a craving – this model will adequately satisfy that desire. A generic ore car produced with the same tooling for over fifty years that any railroad name can be slapped onto its side panel. But the car is not truly prototypical correct for some road names. The car also sports overly thick detail parts (stirrups / grab irons) and is underweight – some adjusting to weight may needed if multiple cars are strung together into a unit train. The brown plastic wheels and unrealistic load are both features I will substitute in the future.An oldie and goodie – but still with some flaws. To see a list of all cars in this series, CLICK HERE

Photograph Citations:

- Vachon, J., photographer. (1941) Iron ore docks at Allouez, Wisconsin. United States Douglas County Wisconsin Allouez, 1941. Aug. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017813258/.

- Vachon, J., photographer. (1941) Iron ore docks at Allouez, Wisconsin. United States Douglas County Wisconsin Allouez, 1941. Aug. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017813317/.

- Vachon, J., photographer. (1941) Ore punchers waiting for cars of iron ore to come in. Allouez, Wisconsin. United States Douglas County Wisconsin Allouez, 1941. Aug. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017813290/.

- Vachon, J., photographer. (1941) Cars of iron ore being emptied into bins on ore docks. Allouez, Wisconsin. United States Douglas County Wisconsin Allouez, 1941. Aug. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017813289/.

- All model photographs are either Copyright Scott Koltz or TroveStar