Per Diem Boxcars

Published: 2020-04-09 - By: gdm

Last updated on: 2022-02-07

Last updated on: 2022-02-07

visibility: Public

The railroad industry suffered through a general shortage of boxcars in the middle 1970's. Low per diem payments- what a railroad pays the registered owner of a car for the use of that car while on its rails- compounded the problem, as per diem payments failed to compensate the owners of the cars for their investment. Several parties within the railroad industry got the Interstate Commerce Commission to approve higher per diem rates for new or rebuilt boxcars as an incentive to invest in new cars.

Several alert venture capital firms capitalized on the new incentive per diem cars. Under a typical arrangement, a leasing company would purchase new boxcars and then lease them to a railroad. The railroad would pay the leasing company either a flat lease rate or a significant portion of the revenue the cars generated for the railroad. The capital firms focused most of their marketing efforts on small Western railroads, especially lumber haulers, under the general plan that the railroad's lumber shippers would load the boxcars with lumber bound for eastern markets, where most of the boxcar shortage existed. The eastern railroads would keep the cars for their own use and thereby rack up enormous per diem revenues for both the leasing railroads and the capital companies. Many shortline railroads that had never rostered interchange equipment in their histories found it economical to have their own cars under these arrangements.

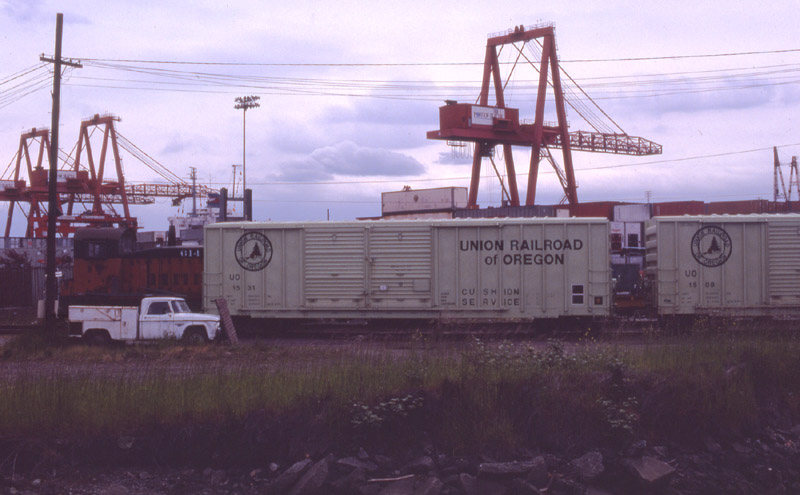

Brae Corporation was one of the two largest capital firms that took advantage of the incentive per diem boxcar craze, and in 1979 the company secured a lease agreement with the Union Railroad of Oregon for fifty new 50-foot, double door boxcars. The railroad numbered the cars in the 1500-series, and they entered service in the nationwide car pool.

The incentive per diem boxcar program suffered a strong backlash in the dawn of the 1980's, eventually resulting in the ICC discontinuing the incentive rates. That, plus depressed traffic levels associated with the tough economic conditions of the time, turned the boxcars shortage into a boxcar surplus. Leasing railroads found themselves swamped with boxcars returned to them by their connecting carriers, and the railroads generally had little choice other than to store the boxcars on their line in hopes of better times to come or turning the cars back to the lessors. The Union Railroad of Oregon did both, first storing as many cars as it could fit on its line and then turning its boxcars back to Brae in 1986. Brae subsequently leased the cars to the Burlington Northern.

Several alert venture capital firms capitalized on the new incentive per diem cars. Under a typical arrangement, a leasing company would purchase new boxcars and then lease them to a railroad. The railroad would pay the leasing company either a flat lease rate or a significant portion of the revenue the cars generated for the railroad. The capital firms focused most of their marketing efforts on small Western railroads, especially lumber haulers, under the general plan that the railroad's lumber shippers would load the boxcars with lumber bound for eastern markets, where most of the boxcar shortage existed. The eastern railroads would keep the cars for their own use and thereby rack up enormous per diem revenues for both the leasing railroads and the capital companies. Many shortline railroads that had never rostered interchange equipment in their histories found it economical to have their own cars under these arrangements.

Brae Corporation was one of the two largest capital firms that took advantage of the incentive per diem boxcar craze, and in 1979 the company secured a lease agreement with the Union Railroad of Oregon for fifty new 50-foot, double door boxcars. The railroad numbered the cars in the 1500-series, and they entered service in the nationwide car pool.

The incentive per diem boxcar program suffered a strong backlash in the dawn of the 1980's, eventually resulting in the ICC discontinuing the incentive rates. That, plus depressed traffic levels associated with the tough economic conditions of the time, turned the boxcars shortage into a boxcar surplus. Leasing railroads found themselves swamped with boxcars returned to them by their connecting carriers, and the railroads generally had little choice other than to store the boxcars on their line in hopes of better times to come or turning the cars back to the lessors. The Union Railroad of Oregon did both, first storing as many cars as it could fit on its line and then turning its boxcars back to Brae in 1986. Brae subsequently leased the cars to the Burlington Northern.